You know you probably shouldn’t be rooting for the hero to go full “scorched earth” on their enemies, but when they do… oh, does it feel good. The whole revenge plot is like that irresistible junk food: satisfying in the moment but leaving you wondering if you’ve just fed your darker instincts. From classics like The Count of Monte Cristo to modern hits like The Boys, revenge tales often have us cheering from the sidelines, wanting the villain to get their well-deserved comeuppance.

But hold up! Just because it feels cathartic doesn’t mean it’s without consequences. The real question is: do these stories simply help us blow off steam, or do they romanticize a behavior that’s harmful? Is the character’s quest for revenge a necessary and understandable drive, or is it sending them spiraling into a pit of self-destruction and moral decay?

First things first: Why do we eat up revenge plots like candy? It’s simple. Fiction gives us the chance to indulge in the fantasy of perfect justice. Real-life justice can be a slow-moving, frustrating process, but in stories, we can watch the villain get obliterated in a poetic, jaw-dropping fashion. It feels like cosmic justice, a wrong finally being made right. If the bad guy has been cruel, corrupt, or—let’s face it—a puppy-kicker, seeing them suffer is like indulging in a much-needed dopamine hit.

The hero is wronged, and you, dear reader, sit there with your popcorn, eagerly awaiting the moment they unleash righteous fury. It’s cathartic. The sense of satisfaction when Edmond Dantès takes down the people who ruined his life, or when Arya Stark crosses off a name on her kill list—chef’s kiss. These moments of retribution feel good because we crave justice. We crave balance in the universe.

But, as they say, with great revenge plots come great consequences. And not all stories handle these consequences with the depth and nuance they deserve.

Now, let’s get into the messy side of revenge stories. The real heart of these tales isn’t just the plot twists or clever traps laid by the protagonist; it’s the emotional, psychological, and moral toll that revenge takes on the character. This is where things can get dark—and interesting.

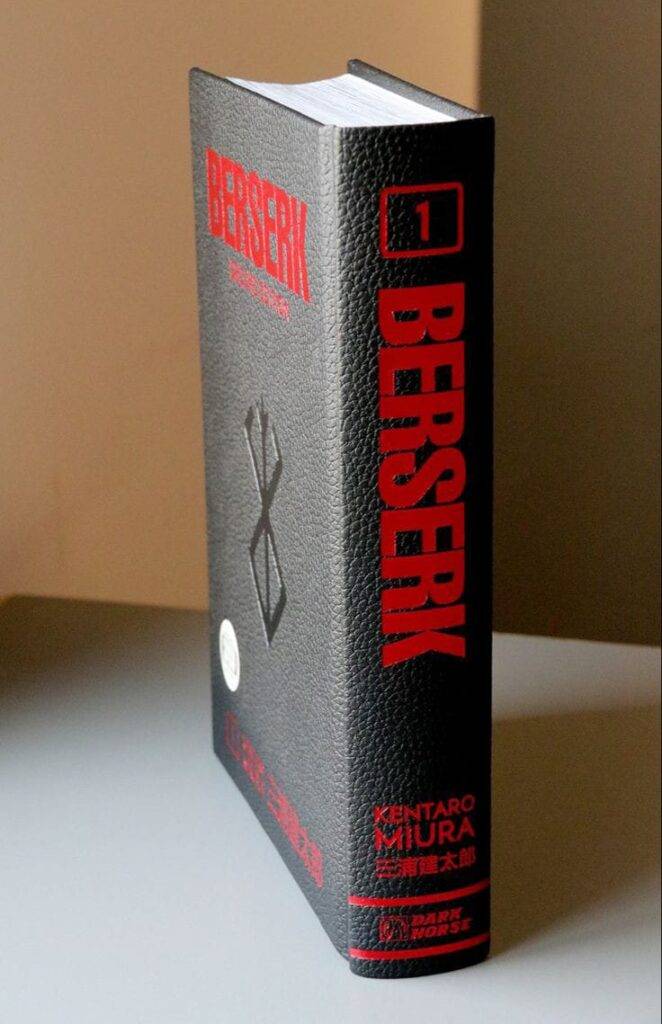

See, in most good revenge stories, the character’s obsessive quest for payback often comes at a massive cost. They don’t just lose the bad guy; they lose parts of themselves, too. A prime example of this is Guts from Berserk. The man has every reason in the world to want to tear Griffith limb from limb. Griffith didn’t just betray him; he destroyed Guts’ world, both physically and emotionally. Revenge feels like the only thing left, but here’s the kicker—Berserk doesn’t frame Guts’ quest as heroic. Sure, he has every right to be angry, but his pursuit of vengeance is practically impossible. He’s fighting god-like beings while abandoning the few good things he still has in life. The story doesn’t glorify his desire for revenge; it highlights the toll it takes on him. As Guts becomes consumed by his quest, he drifts further from humanity, teetering on the edge of becoming a monster himself.

This is what good revenge stories do—they don’t just show the protagonist seeking justice. They explore how that pursuit warps them, how it costs them friendships, happiness, and peace of mind. The journey isn’t about the villain’s punishment, but about how the revenge-seeker transforms—and it’s rarely a good transformation.

Take Billy Butcher from The Boys. He’s got a great reason to be angry, right? His wife’s life was ruined by superheroes, and he’s on a mission to take them down. But in doing so, Butcher becomes increasingly ruthless, harming innocent people, and pushing away those who care about him. He’s not just hurting the bad guys; he’s hurting himself and others, becoming morally questionable—sometimes downright awful. And that’s the whole point: revenge is rarely a clean-cut path. It has collateral damage, and the revenge-seeker can end up being worse off than they were at the start.

Now, here’s where the “revenge is bad” trope can either soar or sink like a badly made soufflé. When done well, stories that explore the pitfalls of revenge show how the pursuit of vengeance can erode a person’s soul. But when it’s done poorly? Oh boy, do audiences tune out.

A lot of viewers aren’t tired of the “revenge is bad” trope itself—they’re tired of seeing it handled poorly. There’s a difference between a nuanced story that shows revenge as a path to self-destruction, and a lazy one that just uses revenge as a plot device. If the protagonist is living a perfectly functional life aside from their desire for revenge, and then suddenly the plot tells us that they’re “just as bad” as the villain—cue eye roll—it’s hard to take seriously. For revenge stories to hit home, the protagonist needs to be shown making bad decisions, becoming increasingly obsessed, and losing their grip on the world around them. The damage revenge causes shouldn’t just be a moral lesson tacked on at the end; it should be central to the character’s arc.

Take Hamlet, for instance. Sure, Hamlet wants revenge for his father’s murder, but that desire consumes him, driving him to alienate everyone he loves, and ultimately leading to a bloodbath where everyone, including Hamlet himself, dies. His obsession ruins him. If Hamlet had just moved on with his life, married Ophelia, and become king, things might have turned out okay. Instead, he spirals into paranoia and madness, losing sight of everything else in the process.

On the flip side, a bad revenge story might feature a villain who’s a cartoonishly evil puppy-kicker, and the protagonist gets told that if they kill this person, they’ll somehow be “just as bad.” Uh, no. If the antagonist is literally a genocidal maniac, audiences aren’t going to buy into the idea that stopping them is morally equivalent to their crimes. In cases like that, the “revenge is bad” trope feels hollow and forced. Sometimes, justice is necessary, and that’s okay.

At the end of the day, revenge stories are fascinating because they tap into something deep in our psyche—the desire for justice, even when it’s messy. But for these stories to be truly impactful, they need to show the complexity of revenge. It’s not just about whether the bad guy deserves to be punished (they usually do); it’s about what happens to the protagonist when they focus solely on that punishment.

When revenge becomes all-consuming, it doesn’t solve anything. It eats away at the person seeking it, warping their sense of right and wrong, and often leaving them worse off than they started. It’s not enough for the story to say, “Revenge is bad.” It needs to show us why it’s bad—through the character’s transformation, their mistakes, and the destruction they leave in their wake.

In well-written stories like Berserk or The Boys, the toll of revenge is clear, and that’s what makes them so powerful. We see that while the villain may deserve every bit of punishment coming their way, the protagonist pays a price, too. If revenge becomes an obsession, it’s not just the villain who gets destroyed—it’s the hero, too.

So, while revenge stories can be incredibly cathartic, they’re also cautionary tales. After all, what’s the point of taking down your enemies if you lose yourself in the process?