Editing pacing can feel anxiety-inducing. Too fast, and your story becomes a mess. Too slow, and your readers might slumber. But you don’t need to exchange scenes you’ve written to fix pacing.

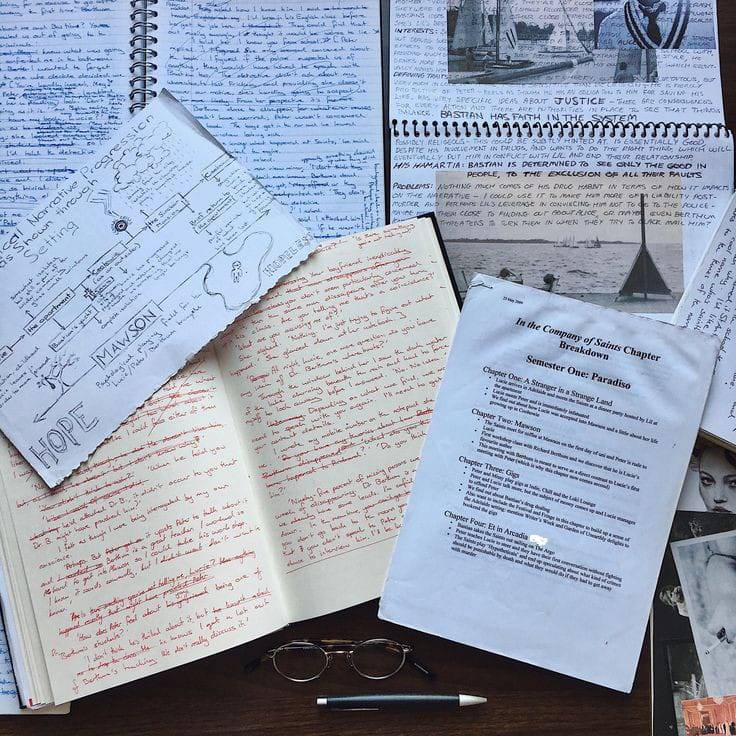

First and foremost: stop thinking about deleting chapters to fix pacing. A blank page doesn’t have pacing. You can’t measure rhythm on something that doesn’t exist. Cutting entire scenes or chapters might seem like a shortcut to tighten the flow, but it often creates new problems, leaving gaping holes in your narrative.

Instead of cutting, focus on reshaping:

– Is the scene’s aim unclear? Clarify its purpose.

– Is it too slow? See how you’re presenting the information. Sometimes rearranging events or tightening descriptions can completely change the pace.

Start by seeing what the scene does for the story—whether it’s growing the plot, revealing character motivations, or setting the tone. If it’s doing a job, it belongs in the book. Your task is to adjust it, not to cut it.

Transitions between scenes can often become bloated, pulling down the pacing. As writers, people tend to over-explain how one event leads to another, worrying that readers will be confused. In reality, readers are smarter than we give them credit for. They don’t need to see every step of the journey from them eating breakfast to them knocking on the door.

Here’s the secret: cut to the action. Start scenes late, and end them early. Let the reader infer the in-between.

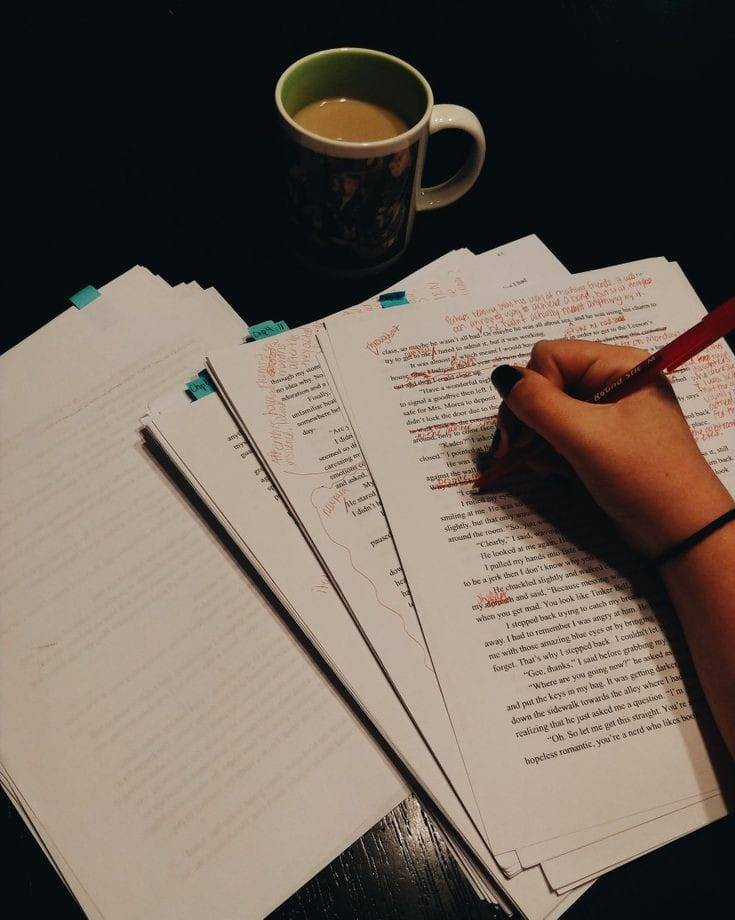

– First draft: overwrite the transitions. Let yourself include every small detail. It’s fine if your draft has 500 words describing them pouring cereal while reflecting on life.

– Second draft: cut it down. Remove everything that doesn’t directly serve the story.

Good dialogue can either quicken or slow your pacing, depending on how you use it. But here’s a trap: going for “perfect” dialogue often leads to unnatural conversations. People don’t talk in perfectly measured sentences. Conversations are messy, full of interruptions, pauses, and shifts in tone. Lean into that mess.

Act it out. Step into your character’s steps. Use interruptions strategically. An argument becomes far more engaging if characters keep cutting each other off.

One example of dialogue done right is in John Wick, the scene where the mob boss tells his son who John Wick is. It’s not just info—it’s tension-building. By the time the dialogue ends, the reader/viewer feels the weight of Wick’s reputation. Then, the story follows through with brutal action. If you’re going to “tell” through dialogue, make sure what comes next pays off.

Sometimes, pacing issues arise from scenes overstaying their welcome. One trick to fixing this is shortening your scenes or chapters, creating a feeling of urgency.

Short scenes shows the effect of quick jump cuts in books. Short chapters also make readers feel like they’re flying through the book, even if the content is thick.

This doesn’t mean every scene needs to be a lightning bolt. Instead, focus on starting scenes as late as possible and leaving as early as you can. Don’t show the full council meeting; show the aftermath, when everyone’s hangry and snapping at each other. Let the fallout happen off-page.

Counterintuitively, slowing down can sometimes improve pacing. Think of how George R.R. Martin builds tension: he introduces stakes at the start of a chapter, then digresses into multi-page descriptions of food, clothing, or weather. The stakes don’t vanish—they linger, building anxiety in the reader.

This works because it forces readers to hold onto the tension. They’re waiting for the hammer to drop, and keeps them on edge.

The key is balance. A few well-placed digressions add depth. Too many, and you risk losing momentum.

Not every detail needs to move the plot forward, but details should always serve the story. A vivid description can immerse readers in your world, making even slow scenes feel purposeful.

Your first instinct might be to doubt everything you’ve written. Don’t. The chunky, awkward draft is part of the process. Write it all: the overwritten transitions, the dialogue, the detailed descriptions. Editing is where the magic happens.

When revising, remember the golden rule: the reader cares about the experience, not the mechanics.

Pacing isn’t about making every scene fast. It’s about rhythm—knowing when to speed up and when to slow down. And remember: the breakfast scene is safe… unless it’s bad cereal. Then it’s toast.